At the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, I was very worried, just like anyone else. I was afraid of what might happen to my family, friends, students, and many others. Coming from Sarajevo, this crisis also triggered memories of the 1990s war in the Balkans–I remembered what it means to live in a time of collective disaster, when everyone you know is affected by a collapse of the social, political and economic system–and I was terrified about the potential effect of the pandemic on the entire world.

But these memories of war in Bosnia also made me realize that what matters most, at the time of an existential crisis, are qualities of our human connections. Things like solidarity, empathy, and kindness. It is so inspiring to see all these new forms of generosity emerging all over the world–from young people doing grocery shopping for the elderly as a way of protecting them, to people getting crafty and producing PPE* for first responders, to fundraising campaigns for people who lost their jobs –we can see that, aside from hoarding food and disinfectants, or profiteering from masks and ventilators, existential crises like COVID-19 also bring out the best in humanity. As much as we are going through a difficult time right now, I believe that this time can be about personal and collective growth, that we see this crisis as an opportunity to create a better world.

Can you tell us more about the Co-MASK initiative and how it was born?

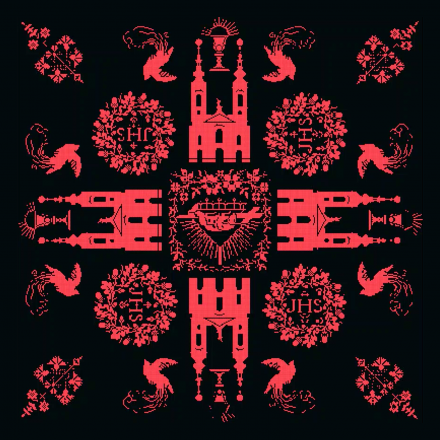

The Co-MASK is a global collaborative effort that I initiated to create fabric masks that promote hope, humanity, and hygiene practices in time of crisis. The project offers instructions in many languages on how to make masks in individual sizes at home, and without a sewing machine. We hope to inspire people around the world to create these masks for their families, friends, and their communities to advocate self-isolation, hygiene practices, and heartfelt human connection. By covering and isolating yourself, you protect others. With their kissing lips and smiling moustaches, these masks are a symbol of hope and love.

The Co-MASK initiative was born at the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, when there was no public awareness about the virus and public authorities had just begun to advocate for “social distancing.” Many were just ignoring these safety recommendations. Many started reacting in fear, avoiding even the eye contact with passers-by. Acts of racism against Asian people increased. Rather than serving collective protection, the notion of social distancing was turning into “social alienation.”

After many sleepless nights, I woke up one morning with the question in mind: How can I be useful in this time? Having a sewing machine at home, I got up and made the first two kissing and smiling mask prototypes. I developed simple instructions for hand-sewing and wrote an email to our community at the School of Architecture and Planning at MIT*, inviting colleagues, students, and alumni to join me in developing this project. I was completely overwhelmed by the outbursts of support. Many started taking on translations into their native languages, asking their family and friends for help, inspiring others to make masks, raising awareness. The collaborations took off beyond MIT, virally so to say, all around the world.

UNESCO’s work focuses a lot on the most vulnerable groups affected by this crisis. It is calling for more dialogue, inclusion, solidarity and tolerance, at all levels. How does this resonate for you?

UNESCO’s work resonates very much in this initiative, from the way we run the project to the instructions and the design itself. The Co-MASK is now developed by a global network of individuals who don’t even know each other in person, but who collaborate across borders to address a shared concern. We want to raise awareness about the risks of COVID-19 infection and the need for physical distancing and self-isolation, while advocating at the same time for solidarity with the most vulnerable in our global community.

This is why the sewing instructions are translated into 25 languages (Arabic, Bosnian, English, Farsi, French, German, Greek, Gujarati, Hebrew, Hindi, Italian, Korean, Marathi, Macedonian, Mandarin, Portuguese, Russian, Slovenian, Spanish, Swahili, Tamil, Turkish, Ukrainian, Urdu, and Vietnamese). The masks can be made with minimal materials and tools, which can be easily found in many locations. Many of our translators have also adapted the content of the sewing instructions to their local contexts, addressing either cultural concerns or availability of certain materials.

We are continuing to develop this global effort: our volunteers are currently developing an open source graphic kit that would enable different NGOs working in refugee camps, deprived communities, and various crisis zones to use these images for free in their advocacy and awareness raising work.

Most importantly, the mask is personalized in terms of both of dimensions and design. The sewing pattern is legible to analphabets. It is based on the mask carrier’s hand dimensions, thus transcending metric and imperial measuring systems, making each mask unique for each person. These person-specific masks give visual form to pluralism. In a world traversed by zones of contact in which lifestyle choices have become targets for reactionary forms of identity paranoia, wearing a mask can be perceived as a threat. The Co-MASK transcends the fear of the other through humour.

You are also a member of the Jury for the UNESCO-Sharjah Prize for Arab Culture. What do you think should be UNESCO’s added value in times like these? What after COVID-19?

The COVID-19 pandemic is projected to have severe effects on the global economy and the associated social inequalities. The severity of these effects gives us just a glimpse into the possible future of life under climate change: it is an alarming call to action, to shift our usual ways of being and working, to act as one united planet. There is no second planet Earth.

The eradication of poverty through sustainable development, peace building and a dialogue across borders, which are at the heart of UNESCO’S mission are as relevant as ever before, if not more. If we are to build more resilient communities, I believe that culture is an essential and powerful vehicle for achieving these aims. Thinking of the rapidly growing numbers of displaced people, I think that we need to rethink some of the parameters on which our crisis responses are built, which mainly focus on supporting the basic biological needs of refugees. I believe that it is imperative to develop tools for the cultural resilience to enable affected communities to overcome adversity and the danger of cultural erasure, social divisions, and marginalization of population on the move to safe grounds. This is where UNESCO, with its established networks and global outreach, can play a vital role.

What would you like this initiative to achieve on a larger scale? What is your ‘dream perspective’?

The Co-MASK initiative was born from a shift in perspective: by turning the focus from fear to creative generosity. Looking at the many DIY* masks that were created and gifted as a result from this initiative, but also the many similar initiatives created by others all over the world, all these efforts are collectively contributing to reaching a shared goal: to protect and unite our global community.

While masks ultimately erase our humanity, by erasing our facial expressions and individuality, the Co-Masks re-inscribe that what has been erased with a message of hope and humour. They show how alienation could be turned into empowerment. For me personally, the Co-MASK is not just a DIY solution, but also an art project. It provides means to expose the inequality of the world we live in and amplify the voices of those who have been silenced. To create art in today’s alienated world means inspiring empathy in future generations that can make them less indifferent to the social costs of maintaining their lifestyles and more open to the voices of others, not as a negotiating technique, but as an indispensable, irreducible, and precarious part of the human chorus. To create projects like the Co-MASK in today’s alienated world means instigating confident idealism in pursuit of a better future.

* PPE = Personal Protection Equipment

* MIT = Massachusetts Institute of Technology

* DIY = Do it yourself