The MIT Program in Art, Culture and Technology (ACT) was recently awarded a $47,305 grant by The Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) as part of the Recordings at Risk program. This funding will allow ACT’s Archivist, Thera Webb, the opportunity to preserve recordings from the MIT Experimental Music Studio.

—

New Music for Computers: Early Recordings from the MIT Experimental Music Studio, 1973-1988

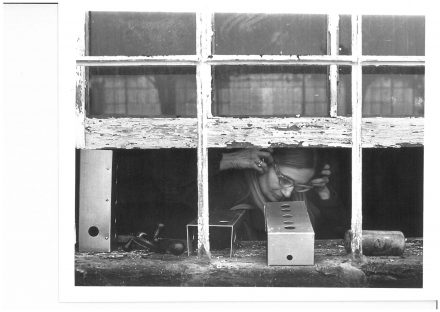

When I started as the archivist for the ACT Archives and Special Collections in 2019, part of familiarizing myself with the archive involved looking in every box in the stacks (over 400!) and reading as many pieces as I could about György Kepes, the Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS), the Visual Arts Program (VAP), and the general history of arts programming at MIT. A number of the boxes I opened contained old reel-to-reel magnetic tapes of varying sizes. I didn’t know of any sound artists in the collection, artists who had produced upwards of 100 recordings while at MIT, so I immediately dove into the collection. And when I saw the titles on some of the reels — “Computer Music for MIT,” “Fantasy Quintet for Piano and Computer 1985,” and “Synapse (for viola and computer) 1976” — I knew I had encountered something special. I grew up hearing stories about my mother’s time studying ethnomusicology in college and her friends who were experimental musicians doing things like hanging microphones in all the rooms at a party and using those recordings to create sound experiences, so I knew the potential of a collection like this.

Through my research, I learned that these recordings came from MIT’s Experimental Music Studio (EMS), run by Barry Vercoe from 1973-1998 as part of the Media Lab. The EMS was one of the great innovating studios in the field of Experimental and Computer Music. Founded in 1973, it was the first facility in the world to dedicate digital computers to the full-time research and composition of computer music. EMS’s members were responsible for developing and significantly improving technologies such as real-time digital synthesis, live keyboard input, graphical score editing, graphical patching languages, synchronization between natural and synthetic sound in composition, and advanced music languages including CSound.

These tapes are not just interesting from a music technology standpoint, though. They contain recordings of compositions and performances by artists like Joan La Barbara, Charles Dodge, Tod Machover, Takashi Koto, Mario Davidovsky, and Jeanne Bamberger, to name only a few. Many of the tapes are titled mysterious things like “Spring 1983 Class Concert Live Recording” or “Etude #4, Computer and Click Tracks,” and we can only imagine what innovative and unusual compositions they might reveal.

It won’t come as a surprise that audio recordings made at MIT in the 70s/80s were done using a wild variety of different technologies. Based on a visual assessment of the tapes, there are variations in tape size, type, speed, number of tracks, and encoding technology. The tapes are in varying states of playability due to their previous storage. Before the EMS collection was donated as part of the Muriel Cooper Visible Language Workshop collection, it sat in a closet forgotten and untouched for years.

Magnetic tape itself degrades at a normal room temperature, and ideally should be stored in a cold storage unit. It is one of the most fragile forms of recording out there, whether reel-to-reel film or sound. Even new audio tape is fragile, as cassettes may break while rewinding and sounds can become warped, and in older reel-to-reel tapes it can be even worse. Reels exposed to a normal range of humidity can swell and the tape develop sticky shed syndrome – where the coating on the tape breaks down and sticks to itself, making playback without damaging the tape nearly impossible if special measures to remove all moisture from the reels prior to playing are not taken. Even then, it’s a one-shot deal: play it and digitize it at the same time, because you probably won’t be able to play it again.

The Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) has been funding digitization projects since 2017 as part of a regranting program with funds from the Mellon Foundation. ACT Archives and Special Collections is proud to have been selected as a grantee for Cycle 7 of the Recordings at Risk grant program. We have received funding to digitize the collection, including an increase in staff hours to properly catalog and populate the metadata for the items so they can be easily found by anybody interested in them. We plan to have parts of the collection online and accessible to the public by the summer of 2021.

When somebody asks me why I became an archivist, I usually answer, “Because I’m nosy.” And it’s true. One of the things I love most about my job is the time I spend exploring the writings and belongings of all kinds of people. Working in the ACT Archives gives me a chance to dive deeply into the creative lives of hundreds of fascinating artists, and experience the unrivaled excitement that comes from uncovering a collection like this. The EMS collection exemplifies the creativity that can be achieved when technology and art work together, the sort of interdisciplinary collaboration that ACT, and MIT, nurtures.

We have been extremely lucky to connect with Hal Wagner, who will be digitizing the collection. Hal is a sound engineer and designer who has been involved in the experimental music community since the early ‘70s, even attending some performances related to the collection. We’ve also been lucky to speak with and receive letters of support for the project from “America’s first synth hero” Suzanne Ciani, Hans Tutschku, Professor of Composition and Director of Electroacoustic Studios at Harvard University, and Nick Patterson, the Music Librarian who initiated the digitization of the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center Archives.

I look forward to keeping you up to date on the digitization process and recommend visiting CLIR’s website to explore the hundreds of digitization projects they’ve funded, both through their Recordings at Risk grant and their Digitizing Hidden Collections grant, with the goal of supporting efforts by collecting institutions to digitize and provide access to collections of rare or unique content.

–Thera Webb, Archivist

twebb@mit.edu